Analogy, relevance realisation and the limits of AI

The falling price and increasing pervasiveness of LLM-based AIs make it easy to fall for the temptation to outsource one’s thinking to machines. Indeed, much of the noise from vendors is aimed at convincing you to do just that. To be sure, there is little harm and some benefit in using AI to assist with drudgework (e.g. minuting meetings) providing one ensures that the output is validated (e.g., Are the minutes accurate? Have nuances been captured? Have off-the-record items been redacted?). However, as the complexity of the task increases, there comes a point where only those with domain expertise can use AIs as assistants effectively.

This is unsurprising to those who know that the usefulness of AI output depends critically on both the quality of the prompt and the ability to assess its output. But it is equally unsurprising that vendors will overstate claims about their products’ capabilities and understate the knowledge and experience required to use them well.

Over the last year or so, a number of challenging benchmarks have been conquered by so-called Large Reasoning Models. This begs the question as to whether there are any inherent limitations to the kinds of cognitive tasks that LLM-based AIs are capable of. At this time it is not possible to answer this question definitively, but one can get a sense for the kinds of tasks that would be challenging for machines by analysing examples of high-quality human thinking.

In a previous article, I described two examples highlighting the central role that analogies play in creative scientific work. My aim in the present piece is to make the case that humans will continue to be better than machines at analogical thinking, at least for the foreseeable future.

–x–

The two analogies I described in my previous article are:

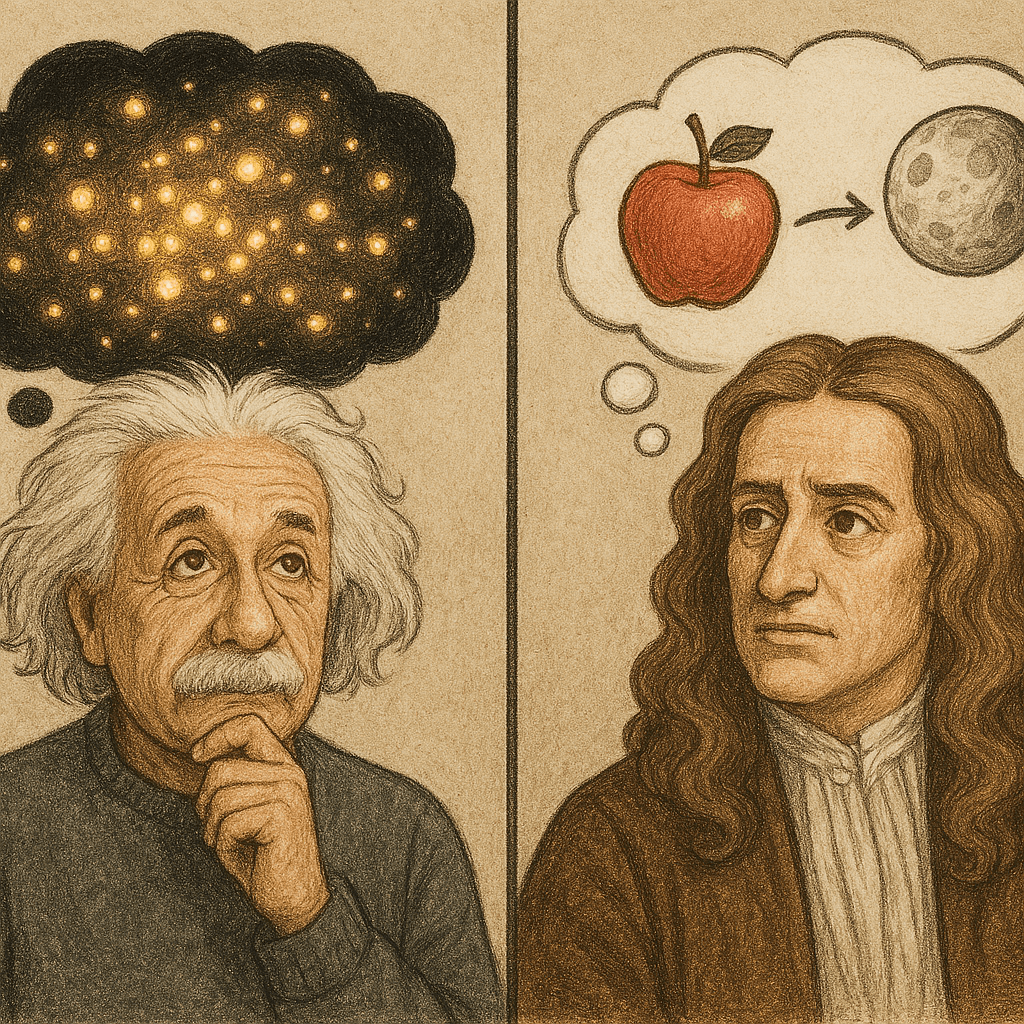

- Newton’s intuition that the fall of an apple on the surface of the earth is analogous to the motion of the moon in its orbit. This enabled him to develop arguments that led to the Universal Law of Gravitation.

- Einstein’s assumption that the energy associated with electromagnetic radiation is absorbed or emitted in discrete packets akin to particles. This enabled him to make an analogy between electromagnetic radiation and an ideal gas, leading to a heuristic justification for the existence of photons (particles of light).

AI evangelists will point to papers that demonstrate analogical reasoning in LLMs (see this paper for example). However, most of these works suggest that AIs are nowhere near as good as humans in analogising. Enthusiasts may then argue that it’s a matter of time before AI catches up. I do not think this will happen because there are no objective criteria by which one can judge an analogy to be logically sound. Indeed, as I discuss below, analogies have to be assessed in terms of relevance rather than truth.

–x–

The logical inconsistency of analogical reasoning is best illustrated by an example drawn from a paper by Gregory Bateson in which he compares the following two syllogisms:

All humans are mortal (premise)

Socrates is human (premise)

Therefore, Socrates is mortal (conclusion)

and

Humans die

Grass dies

Humans are grass

The first syllogism is logically sound because it infers something about a particular member of a set from a statement that applies to all members of that set. The second is unsound because it compares members of different sets based on a shared characteristic – it is akin, for example, to saying mud (member of one set) is chocolate (member of another set) because they are both brown (shared characteristic).

The syllogism in grass, as Bateson called it, is but analogy by another name. Though logically incorrect, syllogisms can give rise to fruitful trains of thought. For example, Bateson’s analogy draws our attention to the fact that both humans and grass are living organisms subject to evolution. This might then lead to thoughts on the co-dependency of grass and humans – e.g. the propagation of grass via the creation of lawns for aesthetic purposes.

Though logically and scientifically unsound, syllogisms in grass can motivate new lines thinking. Indeed, Newton’s apple and Einstein’s photon are analogies akin to Bateson’s syllogism in grass.

–x–

The moment of analogical insight is one of seeing connections between apparently unconnected phenomena. This is a process of sensemaking – i.e. one of taking or framing a problem from a given situation. To do this effectively, one must first understand what aspects of the situation are significant, a process that is called relevance realisation.

In a recent paper, Johannes Jaeger and his colleagues note that living organisms exists in a continual flux of information most of which is irrelevant to their purposes. From this information deluge they must recognise the miniscule fraction of signals or cues that might inform their actions. However, as they note,

“Before they can infer (or decide on) anything, living beings must first turn ill-defined problems into well-defined ones, transform large worlds into small, translate intangible semantics into formalized syntax (defined as the rule-based processing of symbols free of contingent, vague, and ambiguous external referents). And they must do this incessantly: it is a defining feature of their mode of existence.”

This process, which living creatures engage in continually, is the central feature of relevance realisation. Again, quoting from the paper,

“…it is correct to say that “to live is to know” [Editor’s note: a quote taken from this paper by Maturana https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03033910.1988.10557705]. At the very heart of this process is the ability to pick out what is relevant — to delimit an arena in a large world. This is not a formalizable or algorithmic process. It is the process of formalizing the world in Hilbert’s sense of turning ill-defined problems into well-defined ones.”

The process of coming up with useful analogies is, at its heart, a matter of relevance realisation.

–x–

The above may seem far removed from Newton’s apple and Einstein’s photon, but it really isn’t. The fact that Einstein’s bold hypothesis took almost twenty years to be accepted despite strong experimental evidence supporting it suggests that the process of relevance realisation in science is a highly subjective, individual matter. It is only through a (often long) process of socialisation and consensus building that “facts” and “theories” become objective. As Einstein stated in a lecture at UCLA in the 1930s:

“Science as something already in existence, already completed, is the most objective, impersonal thing that we humans know. Science as something coming into being, as a goal, is just as subjectively, psychologically conditioned as are all other human endeavours.”

That is, although established scientific facts are (eventually seen as being) objective, the process by which they are initially formulated depends very much on subjective choices made by an individual scientist. Such choices are initially justified via heuristic or analogical (rather than logical) arguments which draw on commonalities between disparate objects or phenomena. Out of an infinity of possible analogies, the scientist picks one that is most relevant to the problem at hand. And as Jaeger and co have argued, this process of relevance realisation cannot be formalised.

–x–

To conclude: unlike humans, LLMs and AIs in general, are incapable of relevance realisation. So, although LLMs might come up with creative analogies by the thousands, they cannot use them to enhance our understanding of the world. Indeed, good analogies – like those of Newton and Einstein – do not so much solve problems as disclose new ways of knowing. They are examples of intellectual entrepreneurship, a uniquely human activity that machines cannot emulate.

–x–x–

Newton’s apple and Einstein’s photons: on the role of analogy in human cognition

This is the first in a series of reflections on the contrasts between human and machine thinking. My main aim in the present piece is to highlight how humans make sense of novel situations or phenomena for which we have no existing mental models. The basic argument presented here is that we do this by making analogies to what we already know.

Mental models are simplified representations we develop about how the world works. For everyday matters, these representations work quite well. For example, when called upon to make a decision regarding stopping your car on an icy road, your mental model of the interaction between ice and rubber vs road and rubber tells you to avoid sudden braking. Creative work in physics (or any science) is largely about building mental models that offer footholds towards an understanding of the phenomenon being investigated.

So, the question is: how do physicists come up with mental models?

Short answer: By making analogies to things they already know.

–x–

In an article published in 2001, Douglas Hofstadter made the following bold claim:

“One should not think of analogy-making as a special variety of reasoning (as in the dull and uninspiring phrase “analogical reasoning and problem-solving,” a long-standing cliché in the cognitive-science world), for that is to do analogy a terrible disservice. After all, reasoning and problem-solving have (at least I dearly hope!) been at long last recognized as lying far indeed from the core of human thought. If analogy were merely a special variety of something that in itself lies way out on the peripheries, then it would be but an itty-bitty blip in the broad blue sky of cognition. To me, however, analogy is anything but a bitty blip — rather, it’s the very blue that fills the whole sky of cognition — analogy is everything, or very nearly so, in my view.”

The key point he makes is that analogy-making comes naturally to us; we do it several times every day, most often without even being aware of it. For example, this morning when describing a strange odour to someone, I remarked, “It smelt like a mix of burnt toast and horse manure.”

Since analogy enables us to understand the unknown in terms of the known, it should be as useful in creative work as it is in everyday conversation. In the remainder of this article, I will discuss a couple of analogies that led to breakthroughs in physics: one well-known, the other less so.

–x–

Until recently, I had assumed the origin story of the Newton’s theory of gravitation – about a falling apple – to be a myth. I was put right by this very readable history on Newton’s apple tree. Apart from identifying a likely candidate for the tree that bore the fateful fruit, the author presents reminiscences from Newton’s friends and acquaintances about his encounter with the apple. Here’s an account by William Stukely, a close friend of Sir Isaac:

“… After dinner, the weather being warm we went into the garden and drank thea, under the shade of some apple trees, only he and myself. Amidst other discourses, he told me that he was just in the same situation, as when formally the notion of gravity came into his mind. It was occasioned by the fall of an apple, as he sat in a contemplative mood.”

It appears that the creative leap to universal theory of gravitation came from an analogy between a falling apple and a “falling” moon – both being drawn to the centre of the earth. Another account of the Stukely story corroborates this:

“…Amidst other discourse, he told me, he was just in the same situation, as when formerly, the notion of gravitation came into his mind. It was occasioned by the fall of an apple, as he sat in a contemplative mood. Why should that apple always descend perpendicularly to the ground, thought he to him self. Why should it not go sideways or upwards, but constantly to the earth’s centre ? Assuredly, the reason is, that the earth draws it. There must be a drawing power in matter: and the sum of the drawing power in the matter of the earth must be in the earth’s center, not in any side of the earth. Therefore dos this apple fall perpendicularly, or towards the center. If matter thus draws matter, it must be in proportion of its quantity. Therefore the apple draws the earth, as well as the earth draws the apple. That there is a power, like that we here call gravity, which extends its self thro’ the universe…”

Newton’s great of leap intuition was the realisation that what happens at the surface of the earth, insofar as the effect of matter on matter is concerned, is exactly the same as what happens elsewhere in the universe. He realized that both the apple and the moon tend to fall towards the centre of the earth, but the latter doesn’t fall because it has a tangential velocity which exactly counterbalances the force of gravity.

The main point I want to make here is well-summarised in this line from the first article I referenced above: “there can be little doubt that it was through the fall of an apple that Newton commenced his speculations upon the behaviour of gravity.”

–x–

The analogical aspect of the Newton story is easy to follow. However, many analogies associated with momentous advances in physics are not so straightforward because the things physicists deal with are hard to visualise. As Richard Feynman once said when talking about quantum mechanics, “we know we have the theory right, but we haven’t got the pictures [visual mental models] that go with the theory. Is that because we haven’t [found] the right pictures or is it because there aren’t any right pictures?“

He then asks a very important question: supposing there aren’t any right pictures [and the consensus is there aren’t], then is it possible to develop mental models of quantum phenomena?

Yes there is!

However, creating these models requires us to give up the requirement of visualisability: atoms and electrons cannot be pictured as balls or clouds or waves or anything else; they can only be understood through the equations of quantum mechanics. But writing down and solving equations is one thing, understanding their implications is quite another. Many (most?) physicists focus on the former because it’s easier to “shut up and calculate” than develop a feel for what is actually happening.

So, how does one develop an intuition for what is going on when it is not possible to visualise it?

This question brings me to my second analogy. Although it is considerably more complex than Newton’s apple, I hope to give you a sense for the thinking behind it because it is a tour de force of scientific analogy-making.

–x–

The year 1905 has special significance in physics lore. It was the year in which Einstein published four major scientific papers that changed the course of physics.

The third and fourth papers in the series are well known because they relate to the special theory of relativity and mass-energy equivalence. The second builds a theoretical model of Brownian motion – the random jiggling of fine powder scattered on a liquid surface. The first paper of the series provides an intuitive explanation of how light, in certain situations, can be considered to be made up of particles which we now call photons. This paper is not so well-known even though it is the work for which Einstein received the 1921 Nobel Prize for physics. This is the one I’ll focus on as it presents an example of analogy-making par excellence.

To explain the analogy, I’ll first need to set some context around the state of physics at the turn of the last century.

(Aside: Although not essential for what follows, if you have some time I highly recommend you read Feynman’s lecture on the atomic hypothesis, delivered to first year physics students at Caltech in 1962)

–x–

Today, most people do not question the existence of atoms. The situation in the mid1800s was very different. Although there was considerable indirect evidence for the existence of atoms, many influential physicists, such as Ernst Mach, were sceptical. Against this backdrop, James Clerk Maxwell derived formulas relating microscopic quantities such as pressure and temperature of a gas in a container to microscopic variables such as the number of particles and their speed (and energy). In particular, he derived a formula predicting the probability distribution of particle velocities – that is the proportion of particles that have a given velocity. The key assumption Maxwell made in his derivation is that the gas consists of small, inert spherical particles (atoms!) that keep bouncing off each other elastically in random ways – a so-called ideal gas.

The shape of the probability distribution, commonly called the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution, is shown below for a couple of temperatures. As you might expect, the average speed increases with temperature.

I should point out that this was one of the earliest attempts to derive a quantitative link between a macroscopic quantity which we can sense directly and microscopic motions which are inaccessible to our senses. Pause and think about this for a minute. I hope you agree that it is amazing, not the least because it was derived at a time when the atomic hypothesis was not widely accepted as fact.

It turns out that the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution played a key role in Einstein’s argument that light could – in certain circumstances – be modelled as a collection of particles. But to before we get to that, we need to discuss some more physics.

–x–

In the late 19th century it was widely accepted that there are two distinct ways to analyse physical phenomena: as particles (using Newton’s Laws) or as waves (using Maxwell’s Equations for electromagnetic waves, for example).

Particles are localised in space – that is, they are characterised by a position and velocity. Consequently, the energy associated with a particle is localised in space. In contrast, waves are spread out in space and are characterised by a wavelength and frequency as shown in the figure below. Note that the two are inversely related – frequency increases as wavelength decreases and vice versa. The point to note is that, in contrast to particles, the energy associated with a wave is spread out in space.

In the early 1860s, Maxwell established that light is an electromagnetic wave. However visible light represents a very small part of the electromagnetic spectrum which ranges from highly energetic x-rays to low energy radio waves (see the figure below)

The energy of a wave is directly proportional to its frequency – so, high energy X-rays have higher frequencies (and shorter wavelengths) than visible light.

To summarise then, at the turn of the 20th century, the consensus was that light is a wave. This was soon to be challenged from an unexpected direction.

–x–

When an object is heated to a particular temperature, it radiates energy across the entire electromagnetic spectrum. Physically we expect that as the temperature increases, the energy radiated will increase – this is analogous to our earlier discussion of the relationship between the velocity/energy of particles in a gas and the temperature. A practical consequence of this relationship is that blacksmiths can judge the temperature of a workpiece by its colour – red being cooler than white (see chart below).

Keep in mind, though, that visible light is a very small portion of the electromagnetic spectrum: the radiation that a heated workpiece emits extends well beyond the violet and red ends of the visible part of the spectrum.

In the 1880s physicists experimentally established that for a fixed temperature, the distribution of energy emitted by a heated body as a function of frequency is unique. That is – the frequency spread of energy absorbed and emitted by a heated body depends on the temperature alone. The composition of the object does not matter as long as it emits all the energy that it absorbs (a so-called blackbody). The figure below shows the distribution of energy radiated by such an idealised object.

Does the shape of this distribution remind you of something we have seen earlier?

Einstein noticed that the blackbody radiation curve strongly resembles the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution. It is reasonable to assume that others before him would have noticed this too. However, he took the analogy seriously and used it develop a plausibility argument that light could be considered to consist of particles. Although the argument is a little technical, I’ll sketch it out in brief below. Before I do so, I will need to introduce one last physical concept.

–x–

Left to themselves, things tend to move from a state of order to disorder. This applies just as much to atoms as it does to our everyday lives – my workspace tends to move from a state of tidiness to untidiness unless I intervene. In the late 1800s physicists invented a quantitative measure of disorder called entropy. The observation that things tend to become disordered (or messy) if left alone is enshrined in the second law of thermodynamics which states that the entropy of the universe is increasing.

To get a sense for the second law, I urge you to check out this simulation which shows how two gases (red and green) initially separated by a partition tend to mix spontaneously once the partition is removed. The two snapshots below show the initial (unmixed) and equilibrium (mixed) states.

Snapshot 1: Time=0, ordered state, low entropy

Snapshot 2: Time = 452 seconds, disordered (mixed) state, high entropy

The simulation gives an intuitive feel for why a disordered system will never go back to an ordered state spontaneously. It is the same reason that sugar, once mixed into your coffee will never spontaneously turn into sugar crystals again.

Why does the universe behave this way?

The short answer is that there are overwhelmingly more disordered states in the universe than ordered ones. Hence, if left to themselves, things will end up being more disordered (or messy) than they were initially. This is as true of my desk as it is of the mixing of two gases.

Incidentally, the logic of entropy applies to our lives in other ways too. For example, it explains why we have far fewer successes than failures in our lives. This is because success typically requires many independent events to line up in favourable ways, and such a confluence is highly unlikely. See my article on the improbability of success for a deeper discussion of this point.

I could go on about entropy as it is fertile topic, but I ‘ll leave that for another time as I need to get back to my story about Einstein’s photons and finish up this piece.

–x–

Inspired by the similarity between the energy distribution curves of blackbody radiation and an ideal gas, Einstein made the bold assumption that the light bouncing around inside a heated body consisted of an ideal gas of photons. As he noted in his paper, “According to the assumption to be contemplated here, when a light ray is spreading from a point, the energy is not distributed continuously over ever-increasing spaces, but consists of a finite number of energy quanta that are localized in points in space, move without dividing, and can be absorbed or generated only as a whole.“

In essence he assumed that the energy associated with electromagnetic radiation is absorbed or emitted in discrete packets akin to particles. This assumption enabled him to make an analogy between electromagnetic radiation and an ideal gas. Where did the analogy itself come from. The physicist John Rigden notes the following in this article, “what follows comes from Einstein’s deep well of intuition; specifically, his quantum postulate emerges from an analogy between radiation and an ideal gas.” In other words, we have no idea!

Anyway, with the analogy assumed, Einstein compared the change in entropy when an ideal gas consisting of particles is compressed from a volume

to volume

at a constant temperature

(or energy

) to the change in entropy when a “gas of electromagnetic radiation” of average frequency

undergoes a similar compression.

Entropy is typically denoted by the letter , and a change in any physical quantity is conventionally denoted by the Greek letter

, so the change in entropy is denoted by

. The formulas for the two changes in entropy mentioned in the previous paragraph are:

The first of the two formulas was calculated from physics that was well-known at the time (the same physics that led to the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution). The second was based on the analogy that Einstein made between an ideal gas and electromagnetic radiation.

Comparing the exponents in the two formulas, we get:

Which basically tells us that the light contained in the heated container consists of discrete particles that have an energy proportional to the frequency

. The formula relates a wave characteristic (frequency) to the energy of a photon. In Einstein’s original derivation, the quantity denoted by

had a more complicated expression, but he recognised that it was identical to a universal constant identified by Max Planck some years earlier. It is important to note that the connection to Planck’s prior work provided weak evidence for the validity of Einstein’s analogy, but not a rigorous proof.

–x–

As Rigden notes, “Einstein’s “revolutionary” paper has the strange word “heuristic” in the title. This word means that the “point of view” developed – that is, the light particle – is not in itself justified except as it guides thinking in productive ways. Therefore, at the end of his paper, Einstein demonstrated the efficacy of light quanta by applying them to three different phenomena. One of these was the photoelectric effect [which to this day remains] the phenomenon that demonstrated the efficacy of Einstein’s light quantum most compellingly.” (Note: I have not described the other two phenomena here – read Rigden’s article for more about them)

Einstein’s could not justify his analogy theoretically, which is why he resorted to justification by example. Even so many prominent physicists remained sceptical. As Rigden notes, “Einstein’s big idea was universally rejected by contemporary physicists; in fact, Einstein’s light quantum was derisively rejected. When Max Planck, in 1913, nominated Einstein for membership of the Prussian Academy of Science in Berlin, he apologized for Einstein by saying, “That sometimes, as for instance in his hypothesis on light quanta, he may have gone overboard in his speculations should not be held against him.” Moreover, Robert Millikan, whose 1916 experimental data points almost literally fell on top of the straight line predicted for the photoelectric effect by Einstein’s quantum paper, could not accept a corpuscular view of light. He characterized Einstein’s paper as a “bold, not to say reckless, hypothesis of an electro-magnetic light corpuscle of energy hν, which…flies in the face of thoroughly established facts of interference…In his 1922 Nobel address, Niels Bohr rejected Einstein’s light particle. “The hypothesis of light-quanta”, he said, “is not able to throw light on the nature of radiation.” It was not until Arthur Compton’s 1923 X-ray scattering experiment, which showed light bouncing off electrons like colliding billiard balls, that physicists finally accepted Einstein’s idea.”

It took almost twenty years for the implications of Einstein’s bold analogy to be accepted by physicists!

–x–

Perhaps you’re wondering why I’ve taken the time to go through these two analogies in some detail. My reason is simple: I wanted to illustrate the kind of lateral and innovative thinking that humans are uniquely capable of.

I will refrain from making any remarks about whether LLM-based AIs are capable of such thinking. My suspicion – and I’m in good company here – is that the kind of thinking which leads to new insights involves a cognitive realm that has little do with formal reasoning. To put it plainly, although we may describe our ideas using language, the ideas themselves – at least the ones that are truly novel – come from another kind of logic. In the next article in this series, I will speculate on what that logic might be. Then, in a following piece, I will discuss its implications for using AI in ways that augment our capabilities rather than diminish them.

–x—x–

Acknowledgements: the above discussion of Einstein’s analogy are based on this lecture by Douglas Hofstadter and this article by John Rigden. I’d also like to acknowledge Michael Fowler from the University of Virginia for his diffusion simulation (https://galileoandeinstein.phys.virginia.edu/more_stuff/Applets/Diffusion/diffusion.html) which I have used for the entropy explanation in the article.

Meditations on change

Despite our carefully laid plans, the lives of our projects and the projects of our lives often hinge on events we have little control over. Robert Chia stresses this point in his wonderful book, Strategy without Design:

“Ambitious strategic plans, the ‘big picture’ approach that seeks a lasting solution or competitive advantage through large-scale transformations, often end up undermining their own potential effectiveness because they overlook the fine details of everyday happenings at ‘ground zero’ level.”

At one level we know this, yet we act out our personal and work lives as if it were not so.

–x–

In business (and life!) we are exhorted to think before doing. My boss tells me I need to think about my team’s workplan for next year; my wife tells me I need to think about the future. Thinking is at the centre of our strategies, blueprints, plans etc. – the things that supposedly propel our lives into a imagined, better future.

The exhortation to make detailed plans of what we are going to do is a call to think before acting. As Descartes famously wrote, cogito ergo sum: thinking establishes our being.

But is that really so?

–x–

In his posthumously published book, Angels Fear, Gregory Bateson noted that:

“There is a discrepancy of logical type between “think” and “be”. Descartes is trying to jump from the frying pan of thought, ideas, images, opinions, arguments etc., into the fire of existence and action. But that jump itself is unmapped. Between two such contrasting universes there can be no “ergo” – no totally self-evident link. There is no looking before leaping from “cogito” to “sum”

The gap between our plans and reality is analogous to the gap between thought and action. There is ample advice on how to think, but very little on how to act in difficult situations. This gap is, I think, at the heart of the problem that Chia articulates in his writings on emergent approaches to strategy.

Understanding this at the intellectual level is one thing. Grasping it experientially is quite another. For, as they say, there is no better way to learn than through experience.

–x–

A few weeks ago, I attended a 10-day Vipassana course at the Dhamma Bhumi centre in Blackheath. Late April is a beautiful time in the Blue Mountains, with glorious sunshine and autumn colours just starting to turn. A perfect setting to reflect and meditate.

Vipassana, which means insight in Pali, is a meditation technique that revolves around observing the often-transient sensations one encounters across one’s body without reacting to them (for example, that itch at the back of your head right now).

The objective is to develop a sense of equanimity in the face of an ever-changing world. Strangely, it seems to work: the simple act of observing sensations without reacting to them, if done in the right away and for long enough, has a subtle influence on how one perceives and responds to events in the world.

Now, I would not go so far as to say the experience was life changing, but it has certainly made me more aware of the many little incidents and encounters of everyday life and, more importantly, better mediate my reactions to them. That said, it is still very much work in progress.

Buddhist metaphysics suggests that the practice of Vipassana helps one (gradually) understand that it is futile to force change or attempt to bend the world to one’s will. Such acts invariably end in disappointment and frustration; any planned change aimed at achieving a well-defined, stable end-state will miss the mark because the world is Heraclitean: ever-changing and impermanent.

–x–

Heraclitus famously asserted that everything is in motion all the time or all things in the world are constantly changing. Hidden in that statement is a paradox: if everything is changing all the time, then it is nigh impossible to pinpoint what exactly is changing. Why? Because nothing in the universe is stable – see Bateson’s article, Orders of Change, for more on this.

Lewis Carroll describes this paradox in a conversation between Alice and the Caterpillar in Chapter 5 of Alice in Wonderland:

“Who are you?” said the Caterpillar.

This was not an encouraging opening for a conversation. Alice replied, rather shyly, “I—I hardly know, sir, just at present—at least I know who I was when I got up this morning, but I think I must have been changed several times since then.”

“What do you mean by that?” said the Caterpillar sternly. “Explain yourself!”

“I can’t explain myself, I’m afraid, sir,” said Alice, “because I’m not myself, you see.”

If the world is ever-changing then so is one’s own identity, not to mention the identities of everything else around us. This brings up a raft of interesting philosophical questions that I neither have the time nor expertise to confront.

However, I can write about my lived experiences.

–x–

Anapana is a breathing technique taught as a prelude to learning Vipassana. The technique involves focusing on the sensations caused by breathing – for example, the coolness felt above the upper lip on an incoming breath and the corresponding warmth on exhalation.

After a day or two of intense practice I became reasonable at it. So much so that at times deep in a Anapana session, it felt like the observer and the observed were distinct entities: the “I” who was watching me breathe was no longer the me who was being watched.

This was disconcerting. I asked the teacher what was going on.

His terse reply: “don’t worry about it, just do what you are doing.”

At the time his response felt deeply unsatisfying. It was only later I understood: as Wittgenstein famously noted in the final line of the Tractatus: whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.

Some things are best experienced and learnt through experience than spoken (or written about) or taught explicitly.

–x–

An organisation is a complex system in which much of the complexity arises from the multiple pathways of interaction between the people who comprise it. The objective of an organisational strategy (of any kind) is to get all those people working purposefully towards a well-defined set of goals. Such a strategy is invariably accompanied by a roadmap that describes what needs to be done to achieve those objectives. Very often the actions are tightly scripted and controlled by those in charge.

But those who wish to control change are no different from those who believe in a chimerical stability: they are today’s Parmenideans. Many years ago, the cybernetician and organisational theorist, Stafford Beer, wrote:

“The most famous of the believers in change was Heraclitus, working in Ephesus, best known for teaching that everything is in constant flux. It was he who wrote that you cannot step into the same river twice. But just down the road the philosophers of Elea were contending that change is impossible. Parmenides, for example, taught that all change is inconceivable – its appearance an illusion. All this in 500 BC. The argument rages on. Today’s management scone is typified in my experience by people fervidly preaching change to people who fervently embrace change – on condition that nothing alters.”

A little later in the same piece, he notes, “Society is Heraclitian; but Parmenides is in charge“

One could say the same for organisations.

But then, the question is: if tightly scripted and controlled approaches to strategy don’t work, what does?

–x–

The technique of Vipassana is simple, straightforward and can be summarised in a few lines:

The basic procedure is to scan (turn one’s attention to) all parts of the body in sequence, objectively observing the sensations one feels on each part. A sensation is anything that comes to your attention. It could be temperature, humidity, itchiness, pressure, strain, pain etc. Although one is immediately aware of relatively intense sensations itches and pains, one is typically not attuned to the subtle, ephemeral sensations experienced across one’s entire body all the time. The technique forces one to focus on the latter in an equanimous manner – i.e., without reacting to them. Instead, one uses these sensations to guide the pace at which one does the scan. See this reddit post for more.

The simplicity is deceptive.

It was sometime in the latter half of the course – may be day 6 or 7 – I realised that a key aspect of the technique is its indirectness. The sense of balance and equanimity I was practising during meditation was, almost imperceptibly, spilling over into other aspects of my life. I found myself being more relaxed about small things I would normally get upset about. Not always, of course, but more often than I used to.

Habits of a lifetime take a while to change, and the trick to changing them seems to centre around taking an oblique or indirect route.

–x–

In a paper published in 2014, Robert Chia noted that:

“Managing change then is more about small, timely and quiet insertions made to release the immanent forces of change always already present in every organizational situation. Change then appears unexceptionally as a naturally occurring phenomenon; it does not attract undue attention and does not generate unnecessary anxieties. Obliqueness of engagement is key to managing sustainable change in a world that is itself ever-changing.”

From personal experience – and more about that in a moment – I can attest that such an indirect approach to change, which leverages latent possibilities within the organisation, really does work. Akin to natural evolution, it is about repurposing or exapting what is at hand to move in a direction that takes one to a better place.

As Chia wrote,

“The Emergent perspective emphasizes a ‘bottoms up’ approach to change and views outcomes as the result of the cumulative and oftentimes ‘piecemeal’ adaptive actions taken in situ by organizational members in learning to cope with the exigencies of organizational situations.”

So, back to the question I hinted at earlier: how does one act in such a manner?

–x–

Strangely, few if any proponents of the Emergent perspective have offered any advice on how to develop and implement strategy in an indirect manner. As Bateson once noted,

“What is lacking is a theory of action within large complex systems, where the active agent is himself a part and a product of the system.”

A couple of sentences later, Bateson offers a route to a possible solution:

“It seems also that great teachers and therapists avoid all direct attempts to influence the action of others and, instead, try to provide the settings or contexts in which some (usually imperfectly specified) change may occur.”

An indirect approach to change must focus on creating a context in which change can happen of its own accord.

–x–

Participants in a Vipassana course are required to abide by a code of discipline for the entire period of the course At first I thought some of the restrictions were over the top – for example, complete silence, no reading or writing. Now I know that is not so: the rules are necessary for creating a context in which an individual can initiate serious changes in his or her outlook and way of life.

By day three I no longer missed having my phone, journals or reading materials at hand. When the weather permitted, I spent the time between meditation sessions walking on the tracks within the centre compound. On rainy days I would just sit and reflect on the things going on in my head.

Practising the technique seems to evoke all kinds of thoughts, memories and emotions. As we were informed in one of the evening discourses these are all expected natural reactions caused by the process of learning Vipassana in the right context. The serene physical environment and the code of discipline provided that context.

–x–

To be clear, creating a context for good things to happen does not guarantee a specific outcomes, let alone positive ones. The Vipassana experience is highly personal: no two people doing it will have the same experience. Yet, the context is the key because creates conditions in which beneficial outcomes are more likely to occur than harmful ones. This is reflected in the overwhelming number of people who speak positively about the experience.

As I have discussed in an earlier piece , there are many actions from which one might reasonably expect positive changes without knowing upfront, in detail, what exactly those changes are. This is exactly what Bateson was getting at when he wrote about good teachers (or change agents) who are somehow able to create “settings or contexts in which some (usually imperfectly specified) change may occur.”

–x–

In the late 1990s, a group from MIT Media worked on a multi- year project to introduce students in rural Thailand to new learning approaches based on computing technologies. In the early stages of the project, it became evident that standard pedagogical approaches would not work for these students, not because of a lack of ability or intelligence but due a lack of relevance. To address this, the group created a context that would motivate the students to learn. They did this by demonstrating how the technology could help address problems the villagers faced – such as building a dam to store water.

The change in approach made all the difference: once students could relate the new technology to issues that they could relate to, learning came for free. They called this approach Emergent Design.

When I came across the MIT work about a dozen years ago, I realised it could be applied to problems of organisational change (indeed, David Cavallo – one of the MIT team – mentions that specifically in his PhD thesis). Since then, I have applied variations of Emergent Design in distinct organisational settings, ranging from multinationals to not for profits and government agencies. Although the broad approach I took was inspired by the MIT work, it gradually took on a life and identity of its own.

I have described my take on Emergent Design in brief in this article and in detail in this book. However, if I were asked to summarise the key to Emergent Design, I would echo Bateson in saying that it is largely about creating a context in which good stuff can happen. Doing this successfully requires the change agent to develop a deep understanding of the organisation and the way it works, and then initiating small changes that enable it to evolve in a positive direction.

Evolution is a slow process, but far more likely to succeed than revolution (see this article for an elaboration of this point).

–x–

In a lecture on Intelligence, Experience and Evolution, delivered at the Naropa Institute in 1975, Bateson started with the remark, “what goes on inside is what goes on outside.” He was referring to the deep analogy between human learning and natural evolution (see Chapter 6 of his book, Mind and Nature, for an elaboration of the analogy). In essence, learning and evolution are processes of change which are context dependent. Both processes are essentially based on gradual improvement through trial and error, and context plays a key role by constraining successive iterations of trial and error to move in productive directions.

Bateson’s analogy between what goes on in our heads and on the outside assumes an even greater significance for me when I view my experiences over ten years doing organisational change via Emergent Design through the lens of the ten days I spent learning Vipassana in Blackheath. The key lesson it brought home to me is that true, lasting change – whether at the societal, organisational or personal level – is best achieved through a gradual, evolutionary process which mirrors what goes on both on the inside and the outside.

–x–x–